Beach Spectres is a project funded by Matt Parker and the Talking Maths in Public conference's MEGA grant.

It was the idea of Christian Lawson-Perfect, a mathematician and learning software developer at Newcastle University.

What we're planning to do

We want to make the largest aperiodic tiling ever!

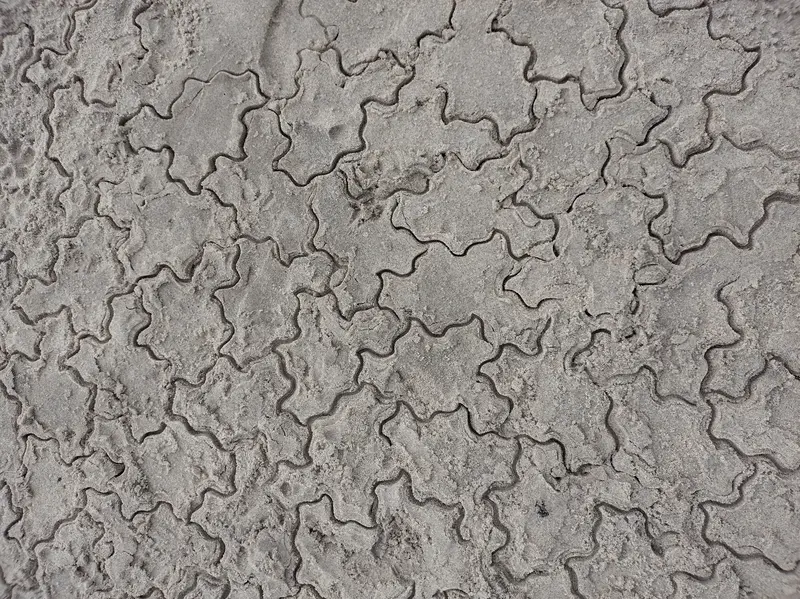

If we'd chosen to lay down actual tiles, we'd be limited by the number of tiles we make. Instead, we're going to make large “cookie cutter” tools in the shape of the spectre monotile, and use them to cover a beach with the aperiodic tiling. There may also be ice cream.

An explanation of aperiodic monotiles that you can handwave your way through at the dinner table

Think about the 2D plane – an infinite, flat surface. How can you completely cover it up? If you’ve got an infinite supply of tiles, can you arrange them together on the plane so that there are no gaps?

If the tiles can be any shape you like, you can put them down however you like and then fill in any gaps with just the right shape. So it’s more interesting to restrict yourself to a certain, finite, set of different tile shapes.

You can do this with infinitely many squares of the same size, or with a mix of equilateral triangles and regular hexagons. If all you’ve got is regular pentagons, you can’t do it: no matter how you arrange them, eventually you’ll end up with a gap that’s too small to put a pentagon tile in.

The next question is: once you’ve put the tiles down, are there any symmetries? If you just used squares, then you can move every tile one space down and it’ll look exactly the same as it did before.

Is it possible to arrange the tiles so that there’s no translation symmetry – so that each point in the plane looks completely unique? This is called a non-periodic tiling.

If you split up a square into a few rectangles with the same proportions, you can produce a non-periodic tiling of the plane by arranging them in a different configuration depending on their position on the plane. But you could also arrange them the same way everywhere, so there would be translation symmetry.

The interesting question is: are there any tiles, or sets of tiles, that can cover the plane, but never with translation symmetry – a truly aperiodic tiling?

The answer is yes: most famously, Roger Penrose found a pair of shapes – a kite and a dart, with specific edge lengths, or alternately a pair of rhombi, marked so that they obey certain edge-matching rules – that together tile the plane, but can never produce translation symmetry. Versions of the shapes which encode the matching rules, with chunks removed and added from the correct edges to force the matching constitute true aperiodic tile sets.

It’s also possible to tile the plane non-periodically using a single tile, called a monotile – for example, the pinwheel tiling consists entirely of copies of a right-angled triangle with sides of length , and – but this shape could also form a periodic tiling, and in order to force the tiling to be aperiodic, matching rules are needed.

What nobody knew until recently was whether there’s a single tile shape that generates only aperiodic tilings, without needing to specify matching rules – an aperiodic monotile.

That’s what David Smith, Joseph Samuel Myers, Craig S. Kaplan, and Chaim Goodman-Strauss have found. They’ve found a shape that can tile the plane, which is the easy part, and then proved that it must tile aperiodically. They came up with a new technique for proving this – actually, two: they proved it twice, just to be sure.

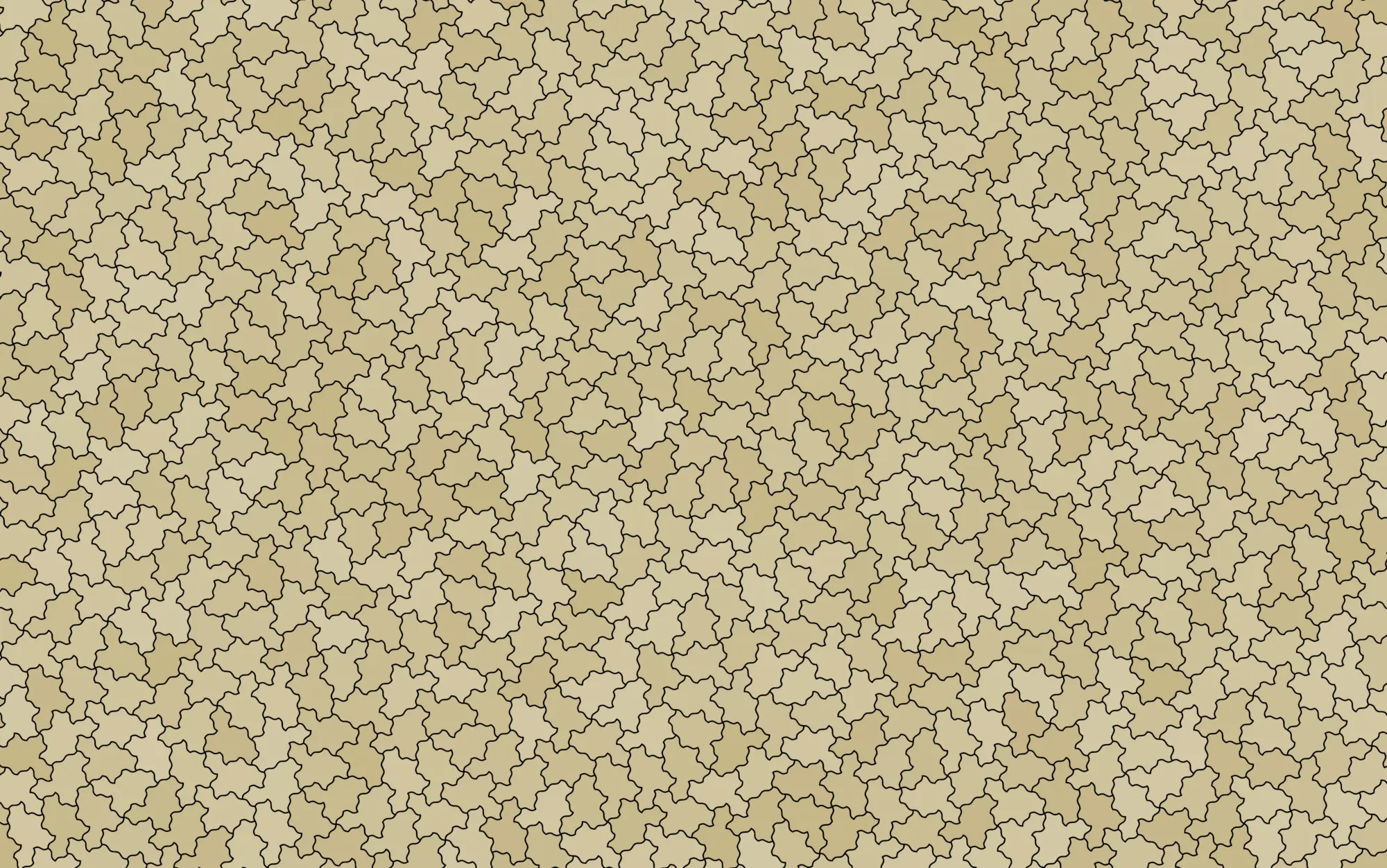

They first discovered the "hat" monotile, which only tiles the plane if some of the copies are flipped around. Some people thought that didn't count as a real monotile, so they kept thinking and found the Spectre. It tiles the plane aperiodically and its edges have no reflective symmetry, so you can't have a mix of flipped and unflipped tiles in the same tiling.

Because the wobbly sides make it look a bit spooky, they called it the "Spectre".

Smith, Myers, Kaplan and Goodman-Strauss published their findings and have had them reviewed by their mathematical peers. They've put together a webpage with links to the paper, images of the tiling, and interactive tools.